- By admin

- In SilkRoadKnowledge

- 2024-04-29

Silk Road horses and camels

The people [of Ferghana]...have...many good horses.

The horses sweat blood and come from the stock of the "heavenly horse."

--Zhang Qian, 2nd c. BCE (tr. F. Hirth)

The camel...manifests its merit in dangerous places; it has

secret understanding of springs and sources; subtle indeed is its knowledge.

-- Kuo P'u, 3rd c. CE (tr. E.H. Schafer)

Crying camels come out of the Western Regions,

Tail to muzzle linked, one after the other.

The posts of Han sqeep them away throught he clouds,

The men of Hu lead them over the snow.

-- Mei Yao-ch'en, 11th c. CE (tr. Schafer)

Rock drawing of Juan-juan warrior (?)

Rock drawing of Juan-juan warrior (?)

Found at Salkhitiyn Shuuduun Zost, near Tsambagarav Uul

5th - early 6th century

There is still some debate regarding the identity of the culture responsible for these striking drawings. Part of the difficulty in dating these drawings is the fact that Salkhitiyn Shuuduun Zost, a site in Mongolia, has been a popular location for petroglyph creation ever since the Neolithic period (see alternate view), and there are many places where the drawings have overlapped, faded or been altered.

Scholarly consensus originally dated these horsemen to sometime in the 6th - 7th centuries CE, a time corresponding to the period of Tujue control of the Mongolian steppes. In 1990 this date was reappraised when similarities were pointed out between the armor depicted on these horsemen and that known to have been worn by the Juan-juan. Though no firm consensus has been reached, today the rock drawings are generally dated to the 5th - early 6th century and credited to the Juan-juan.

Animals are an essential part of the story of the Silk Road. While those such as sheep and goats provided many communities the essentials of daily life, horses and camels both supplied local needs and were keys to the development of international relations and trade. Even today in Mongolia and some areas of Kazakhstan, the rural economy may still be very intimately connected with the raising of horses and camels; their milk products and, even occasionally, their meat, are a part of the local diet. The distinct natural environments of much of Inner Asia encompassing vast steppe lands and major deserts made those animals essential for the movement of armies and trade. The animals' value to the neighboring sedentary societies, moreover, meant that they themselves were objects of trade. Given their importance, the horse and camel occupied a significant place in the literatures and representational art of many peoples along the Silk Road.

Belt buckle featuring horse and rider

Belt buckle featuring horse and rider

Parthian, 2nd-3rd century AD

Leaded bronze

Height: 7 cm

Width: 7.2 cm

Acquisition number: #ANE 139205 Image courtesy of the British Museum (copyright reserved)

This belt buckle depicts a helmeted Parthian horseman armed with bearing a large ring in his left hand, while his right hand rests on the back of his saddle. Like the rider, the horse is highly stylized. Studies of Parthian statuary indicate that such flamboyant belt buckles were common during this times, particularly those found on the statues recovered from the contemporary caravan city of Hatra on the western edge of the Parthian Empire, in northern Mesopotamia.1

Not much remains of any Hellenistic influence in this piece, yet neither do we see strong reference to the pre-Seleucid Achaemenid culture, which so interested the Parthians in the later centuries. Rather, this belt buckle speaks to us of the nomadic culture of peoples who settled in the northern parts of Parthia. These peoples settled in the lands east of the Caspian Sea, and contributed much to Parthian culture as they were integrated into a more sedentary lifestyle.

(1) See the British Museum web page dedicated to this object.

With the development of the light, spoked wheel in the second millennium BCE, horses came to be used to draw military chariots, remains of which have been found in tombs all across Eurasia. The use of horses as cavalry mounts probably spread eastward from Western Asia in the early part of the first millennium BCE. Natural conditions suitable for raising horses large and strong enough for military use were to be found in the steppes and mountain pastures of Northern and Central Inner Asia, but generally not in the regions best suited for intensive agriculture such as Central China. Marco Polo would note much later regarding the lush mountain pastures: "Here is the best pasturage in the world; for a lean beast grows fat here in ten days" (Latham tr.). Thus, well before the famous journey to the west of Zhang Qian (138-126 BCE), sent by the Han emperor to negotiate an alliance against the nomadic Xiongnu, China had been importing horses from the northern nomads.

The relations between the Xiongnu and China have traditionally been seen as marking the real start of the Silk Road, since it was in the second century BCE that we can document large quantities of silk being sent on a regular basis to the nomads as a way of keeping them from invading China and also as a means of payment for the horses and camels needed by the Chinese armies. Zhang Qian's report about the Western Regions and the rebuff of initial Chinese overtures for allies prompted energetic measures by the Han to extend their power to the west. Not the least of the goals was to secure a supply of the "blood-sweating" "heavenly" horses of Ferghana.

Related destinations

Why Choose Us?

We are the top Silk Road tour operator based in Dunhuang, China. We focus on providing well designed Silk Road China Tours with resonable price and thoughtful service.

- Easy & carefree booking

- The best value

- Great travel experience

- Locally operated

Hot Tours

-

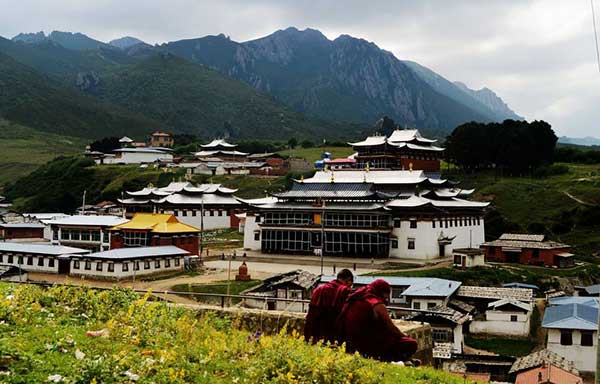

6 days Gansu tour to Binglingsi, Xiahe and Langmusi

Tour type : Private tour Price : from *** Destinations : Lanzhou - linxia - Xiahe - Langmusi - Hezuo - Lanzhou -

12 Days Gansu Highlights Tour

Tour type : Private tour Price : from *** Destinations : Xian – Tianshui – Lanzhou – Xiahe – Langmusi – Hezuo – Zhangye – Jiayuguan - Dunhuang -

10 Days Silk Road Classic Tour

Tour type : Private tour Price : from *** Destinations : Xian - Zhangye - Jiayuguan - Dunhuang - Turpan - Urumqi -

5 Days Zhangye - Alxa youqi Highlights Tour

Tour type : Private Tour Price : from *** Destinations : Zhangye - Alax youqi - Zhangye